Ping Pong Video Games

Posted : admin On 8/11/2019May 28, 2018 Buffalo Games PlingPong- The Fast-Paced Ping Pong Game of Skill, Luck and Strategy. Related video shorts. Page 1 of 1 Start Over Page 1 of 1. Upload your video. Previous page. Buffalo Games PlingPong- The Fast-Paced Ping Pong Game of Skill, Luck and Strategy. Manufacturer Video. Ping Pong Chaos is developed by New Eich Games. The game is available as a web browser game and as an iOS app. Mobile Apps Categorization Skill » 2 Player » Ping Pong Chaos More Information About Ping Pong Chaos. Ping Pong Chaos is an exciting 2. Pong Game Welcome to PongGame.org, In this site, you can find many free versions of the game, one of the first video games ever created. In the game below, use the mouse or keyboard K and M keys to control the paddle, the first player to get 10 points will win the game. Rackets at the ready! VR Ping Pong Pro is the follow up to the hit table tennis simulator of 2016, VR Ping Pong. Test your skills with a variety of challenging game modes, as you rise up the ranks to become the true Ping Pong Pro!

This version of pong reminds squash a bit, the two paddles are in a cubical room, except for that, the rules are exactly the same as the classic pong game, you should hit the ball with your paddle and move it to the opponents ground, you will lose a point once you missed a ball.

| Pong | |

|---|---|

An upright cabinet of Pong on display at the Neville Public Museum of Brown County | |

| Developer(s) | Atari |

| Publisher(s) | Atari |

| Designer(s) | Allan Alcorn |

| Platform(s) |

|

| Release | 29 November 1972 |

| Genre(s) | Sports |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

| Cabinet | Upright |

| CPU | Discrete |

| Sound | Monaural (mono) |

| Display | Horizontal orientation, black-and-white raster display, standard resolution |

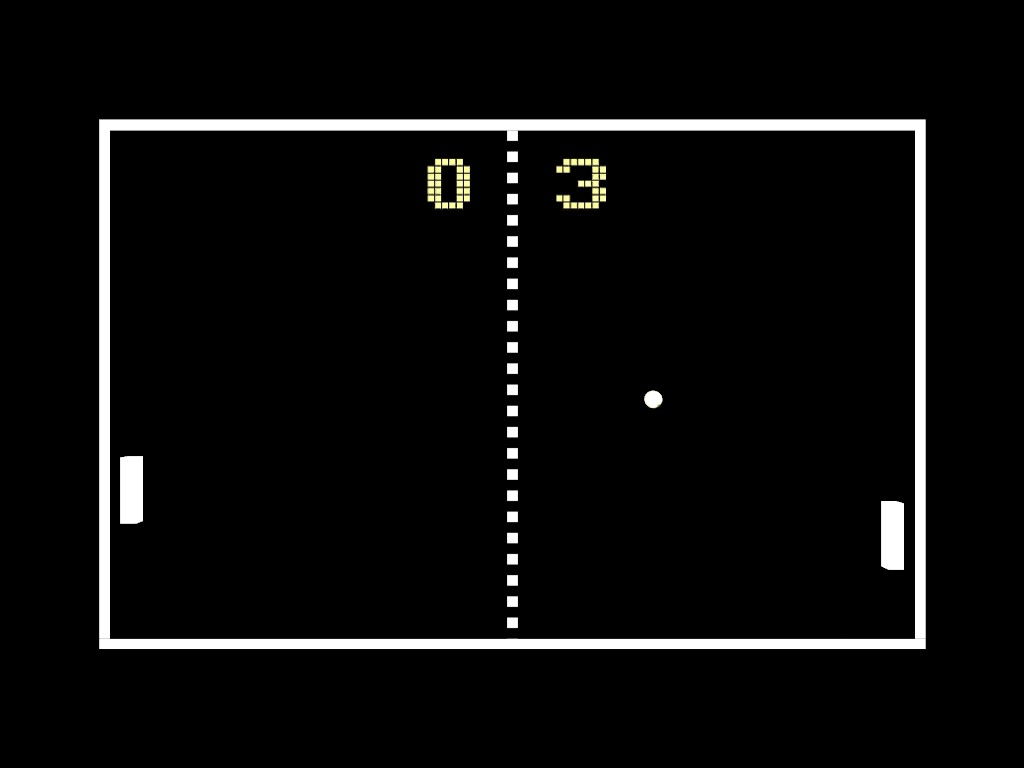

Pong is one of the earliest arcade video games. It is a table tennis sports game featuring simple two-dimensional graphics. The game was originally manufactured by Atari, which released it in 1972. Allan Alcorn created Pong as a training exercise assigned to him by Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell. Bushnell based the idea on an electronic ping-pong game included in the Magnavox Odyssey; Magnavox later sued Atari for patent infringement. Bushnell and Atari co-founder Ted Dabney were surprised by the quality of Alcorn's work and decided to manufacture the game.

Pong was the first commercially successful video game, which helped to establish the video game industry along with the first home console, the Magnavox Odyssey. Soon after its release, several companies began producing games that copied its gameplay, and eventually released new types of games. As a result, Atari encouraged its staff to produce more innovative games. The company released several sequels which built upon the original's gameplay by adding new features. During the 1975 Christmas season, Atari released a home version of Pong exclusively through Sears retail stores. It also was a commercial success and led to numerous copies. The game has been remade on numerous home and portable platforms following its release. Pong is part of the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. due to its cultural impact.

- 2Development and history

- 3Impact and legacy

Gameplay[edit]

Pong is a two-dimensionalsports game that simulates table tennis. The player controls an in-game paddle by moving it vertically across the left or right side of the screen. They can compete against another player controlling a second paddle on the opposing side. Players use the paddles to hit a ball back and forth. The goal is for each player to reach eleven points before the opponent; points are earned when one fails to return the ball to the other.[1][2][3]

Development and history[edit]

Pong was the first game developed by Atari.[4][5] After producing Computer Space, Bushnell decided to form a company to produce more games by licensing ideas to other companies. The first contract was with Bally Manufacturing Corporation for a driving game.[3][6] Soon after the founding, Bushnell hired Allan Alcorn because of his experience with electrical engineering and computer science; Bushnell and Dabney also had previously worked with him at Ampex. Prior to working at Atari, Alcorn had no experience with video games.[7] To acclimate Alcorn to creating games, Bushnell gave him a project secretly meant to be a warm-up exercise.[7][8] Bushnell told Alcorn that he had a contract with General Electric for a product, and asked Alcorn to create a simple game with one moving spot, two paddles, and digits for score keeping.[7] In 2011, Bushnell stated that the game was inspired by previous versions of electronic tennis he had played before; Bushnell played a version on a PDP-1 computer in 1964 while attending college.[9] However, Alcorn has claimed it was in direct response to Bushnell's viewing of the Magnavox Odyssey's Tennis game.[7] In May 1972, Bushnell had visited the Magnavox Profit Caravan in Burlingame, California where he played the Magnavox Odyssey demonstration, specifically the table tennis game.[10][11] Though he thought the game lacked quality, seeing it prompted Bushnell to assign the project to Alcorn.[9]

Alcorn first examined Bushnell's schematics for Computer Space, but found them to be illegible. He went on to create his own designs based on his knowledge of transistor–transistor logic and Bushnell's game. Feeling the basic game was too boring, Alcorn added features to give the game more appeal. He divided the paddle into eight segments to change the ball's angle of return. For example, the center segments return the ball a 90° angle in relation to the paddle, while the outer segments return the ball at smaller angles. He also made the ball accelerate the longer it remained in play; missing the ball reset the speed.[3] Another feature was that the in-game paddles were unable to reach the top of the screen. This was caused by a simple circuit that had an inherent defect. Instead of dedicating time to fixing the defect, Alcorn decided it gave the game more difficulty and helped limit the time the game could be played; he imagined two skilled players being able to play forever otherwise.[7]

Three months into development, Bushnell told Alcorn he wanted the game to feature realistic sound effects and a roaring crowd.[7][12] Dabney wanted the game to 'boo' and 'hiss' when a player lost a round. Alcorn had limited space available for the necessary electronics and was unaware of how to create such sounds with digital circuits. After inspecting the sync generator, he discovered that it could generate different tones and used those for the game's sound effects.[3][7] To construct the prototype, Alcorn purchased a $75 Hitachiblack-and-white television set from a local store, placed it into a 4-foot (1.2 m) wooden cabinet, and soldered the wires into boards to create the necessary circuitry. The prototype impressed Bushnell and Dabney so much that they felt it could be a profitable product and decided to test its marketability.[3]

In August 1972, Bushnell and Alcorn installed the Pong prototype at a local bar, Andy Capp's Tavern.[13][14][15][16] They selected the bar because of their good working relation with the bar's owner and manager, Bill Gaddis;[17] Atari supplied pinball machines to Gaddis.[5] Bushnell and Alcorn placed the prototype on one of the tables near the other entertainment machines: a jukebox, pinball machines, and Computer Space. The game was well received the first night and its popularity continued to grow over the next one and a half weeks. Bushnell then went on a business trip to Chicago to demonstrate Pong to executives at Bally and Midway Manufacturing;[17] he intended to use Pong to fulfill his contract with Bally, rather than the driving game.[3][4] A few days later, the prototype began exhibiting technical issues and Gaddis contacted Alcorn to fix it. Upon inspecting the machine, Alcorn discovered that the problem was the coin mechanism was overflowing with quarters.[17]

After hearing about the game's success, Bushnell decided there would be more profit for Atari to manufacture the game rather than license it, but the interest of Bally and Midway had already been piqued.[4][17] Bushnell decided to inform each of the two groups that the other was uninterested—Bushnell told the Bally executives that the Midway executives did not want it and vice versa—to preserve the relationships for future dealings. Upon hearing Bushnell's comment, the two groups declined his offer.[17] Bushnell had difficulty finding financial backing for Pong; banks viewed it as a variant of pinball, which at the time the general public associated with the Mafia. Atari eventually obtained a line of credit from Wells Fargo that it used to expand its facilities to house an assembly line.[18] The company announced Pong on 29 November 1972.[19][20] Management sought assembly workers at the local unemployment office, but was unable to keep up with demand. The first arcade cabinets produced were assembled very slowly, about ten machines a day, many of which failed quality testing. Atari eventually streamlined the process and began producing the game in greater quantities.[18] By 1973, they began shipping Pong to other countries with the aid of foreign partners.[21]

Home version[edit]

After the success of Pong, Bushnell pushed his employees to create new products.[4][22] In 1974, Atari engineer Harold Lee proposed a home version of Pong that would connect to a television: Home Pong. The system began development under the codename Darlene, named after an attractive female employee at Atari. Alcorn worked with Lee to develop the designs and prototype and based them on the same digital technology used in their arcade games. The two worked in shifts to save time and money; Lee worked on the design's logic during the day, while Alcorn debugged the designs in the evenings. After the designs were approved, fellow Atari engineer Bob Brown assisted Alcorn and Lee in building a prototype. The prototype consisted of a device attached to a wooden pedestal containing over a hundred wires, which would eventually be replaced with a single chip designed by Alcorn and Lee; the chip had yet to be tested and built before the prototype was constructed. The chip was finished in the latter half of 1974, and was, at the time, the highest-performing chip used in a consumer product.[22]

Bushnell and Gene Lipkin, Atari's vice-president of sales, approached toy and electronic retailers to sell Home Pong, but were rejected. Retailers felt the product was too expensive and would not interest consumers.[23] Atari contacted the Sears Sporting Goods department after noticing a Magnavox Odyssey advertisement in the sporting goods section of its catalog. Atari staff discussed the game with a representative, Tom Quinn, who expressed enthusiasm and offered the company an exclusive deal. Believing they could find more favorable terms elsewhere, Atari's executives declined and continued to pursue toy retailers. In January 1975, Atari staff set up a Home Pong booth at a toy trade fair in New York City, but was unsuccessful in soliciting orders due to the fact that they did not know that they needed a private showing.[22][23]

While at the show, they met Quinn again, and, a few days later, set up a meeting with him to obtain a sales order. In order to gain approval from the Sporting Goods department, Quinn suggested Atari demonstrate the game to executives in Chicago. Alcorn and Lipkin traveled to the Sears Tower and, despite a technical complication in connection with an antenna on top of the building which broadcast on the same channel as the game, obtained approval. Bushnell told Quinn he could produce 75,000 units in time for the Christmas season; however, Quinn requested double the amount. Though Bushnell knew Atari lacked the capacity to manufacture 150,000 units, he agreed.[22] Atari acquired a new factory through funding obtained by venture capitalistDon Valentine. Supervised by Jimm Tubb, the factory fulfilled the Sears order.[24] The first units manufactured were branded with Sears' 'Tele-Games' name. Atari later released a version under its own brand in 1976.[25]

Lawsuit from Magnavox[edit]

The success of Pong attracted the attention of Ralph Baer, the inventor of the Magnavox Odyssey, and his employer, Sanders Associates. Sanders had an agreement with Magnavox to handle the Odyssey's sublicensing, which included dealing with infringement on its exclusive rights. However, Magnavox had not pursued legal action against Atari and numerous other companies that released Pong clones.[26] Sanders continued to apply pressure, and in April 1974 Magnavox filed suit against Atari, Allied Leisure, Bally Midway and Chicago Dynamics.[27] Magnavox argued that Atari had infringed on Baer's patents and his concept of electronic ping-pong based on detailed records Sanders kept of the Odyssey's design process dating back to 1966. Other documents included depositions from witnesses and a signed guest book that demonstrated Bushnell had played the Odyssey's table tennis game prior to releasing Pong.[26][28] In response to claims that he saw the Odyssey, Bushnell later stated that, 'The fact is that I absolutely did see the Odyssey game and I didn't think it was very clever.'[29]

After considering his options, Bushnell decided to settle with Magnavox out of court. Bushnell's lawyer felt they could win; however, he estimated legal costs of US$1.5 million, which would have exceeded Atari's funds. Magnavox offered Atari an agreement to become a licensee for US$700,000. Other companies producing 'Pong clones'—Atari's competitors—would have to pay royalties. In addition, Magnavox would obtain the rights to Atari products developed over the next year.[26][28] Magnavox continued to pursue legal action against the other companies, and proceedings began shortly after Atari's settlement in June 1976. The first case took place at the district court in Chicago, with Judge John Grady presiding.[26][28][30] To avoid Magnavox obtaining rights to its products, Atari decided to delay the release of its products for a year, and withheld information from Magnavox's attorneys during visits to Atari facilities.[28]

Impact and legacy[edit]

The Pong arcade games manufactured by Atari were a great success. The prototype was well received by Andy Capp's Tavern patrons; people came to the bar solely to play the game.[4][17] Following its release, Pong consistently earned four times more revenue than other coin-operated machines.[31] Bushnell estimated that the game earned US$35–40 per day, which he described as nothing he'd ever seen before in the coin-operated entertainment industry at the time.[9] The game's earning power resulted in an increase in the number of orders Atari received. This provided Atari with a steady source of income; the company sold the machines at three times the cost of production. By 1973, the company had filled 2,500 orders, and, at the end of 1974, sold more than 8,000 units.[31] The arcade cabinets have since become collector's items with the cocktail-table version being the rarest.[32] Soon after the game's successful testing at Andy Capp's Tavern, other companies began visiting the bar to inspect it. Similar games appeared on the market three months later, produced by companies like Ramtek and Nutting Associates.[33] Atari could do little against the competitors as they had not initially filed for patents on the solid state technology used in the game. When the company did file for patents, complications delayed the process. As a result, the market consisted primarily of 'Pong clones'; author Steven Kent estimated that Atari had produced less than a third of the machines.[34] Bushnell referred to the competitors as 'Jackals' because he felt they had an unfair advantage. His solution to competing against them was to produce more innovative games and concepts.[33][34]

Home Pong was an instant success following its limited 1975 release through Sears; around 150,000 units were sold that holiday season.[35][36] The game became Sears' most successful product at the time, which earned Atari a Sears Quality Excellence Award.[36] Similar to the arcade version, several companies released clones to capitalize on the home console's success, many of which continued to produce new consoles and video games. Magnavox re-released their Odyssey system with simplified hardware and new features, and would later release updated versions. Coleco entered the video game market with their Telstar console; it features three Pong variants and was also succeeded by newer models.[35] Nintendo released the Color TV Game 6 in 1977, which plays six variations of electronic tennis. The next year, it was followed by an updated version, the Color TV Game 15, which features fifteen variations. The systems were Nintendo's entry into the home video game market and the first to produce themselves—they had previously licensed the Magnavox Odyssey.[37] The dedicated Pong consoles and the numerous clones have since become varying levels of rare; Atari's Pong consoles are common, while APF Electronics' TV Fun consoles are moderately rare.[38] Prices among collectors, however, vary with rarity; the Sears Tele-Games versions are often cheaper than those with the Atari brand.[35]

Several publications consider Pong the game that launched the video game industry as a lucrative enterprise.[8][25][39] Video game author David Ellis sees the game as the cornerstone of the video game industry's success, and called the arcade game 'one of the most historically significant' titles.[4][32] Kent attributes the 'arcade phenomenon' to Pong and Atari's games that followed it, and considers the release of the home version the successful beginning of home video game consoles.[33][36] Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton of Gamasutra referred to the game's release as the start of a new entertainment medium, and commented that its simple, intuitive gameplay made it a success.[25] In 1996 Next Generation named it one of the 'Top 100 Games of All Time', recounting that 'Next Generation staff ignor[ed] hundreds of thousands of dollars of 32-bit software to play Pong for hours when the Genesis version was released.'[40]Entertainment Weekly named Pong one of the top ten games for the Atari 2600 in 2013.[41] Many of the companies that produced their own versions of Pong eventually became well-known within the industry. Nintendo entered the video game market with clones of Home Pong. The revenue generated from them—each system sold over a million units—helped the company survive a difficult financial time, and spurred them to pursue video games further.[37] After seeing the success of Pong, Konami decided to break into the arcade game market and released its first title, Maze. Its moderate success drove the company to develop more titles.[42]

Bushnell felt that Pong was especially significant in its role as a social lubricant, since it was multiplayer-only and did not require each player to use more than one hand: 'It was very common to have a girl with a quarter in hand pull a guy off a bar stool and say, 'I'd like to play Pong and there's nobody to play.' It was a way you could play games, you were sitting shoulder to shoulder, you could talk, you could laugh, you could challenge each other .. As you became better friends, you could put down your beer and hug. You could put your arm around the person. You could play left-handed if you so desired. In fact, there are a lot of people who have come up to me over the years and said, 'I met my wife playing Pong,' and that's kind of a nice thing to have achieved.'[43]

Sequels and remakes[edit]

Bushnell felt the best way to compete against imitators was to create better products, leading Atari to produce sequels in the years followings the original's release: Pong Doubles, Super Pong, Ultra Pong, Quadrapong, and Pin-Pong.[2] The sequels feature similar graphics, but include new gameplay elements; for example, Pong Doubles allows four players to compete in pairs, while Quadrapong—also released by Kee Games as Elimination—has them compete against each other in a four way field.[44][45] Bushnell also conceptualized a free-to-play version of Pong to entertain children in a Doctor's office. He initially titled it Snoopy Pong and fashioned the cabinet after Snoopy's doghouse with the character on top, but retitled it to Puppy Pong and altered Snoopy to a generic dog to avoid legal action. Bushnell later used the game in his chain of Chuck E. Cheese's restaurants.[2][46][47][48][49] In 1976, Atari released Breakout, a single-player variation of Pong where the object of the game is to remove bricks from a wall by hitting them with a ball.[50] Like Pong, Breakout was followed by numerous clones that copied the gameplay, such as Arkanoid, Alleyway, and Break 'Em All.[51]

Atari remade the game on numerous platforms. In 1977, Pong and several variants of the game were featured in Video Olympics, one of the original release titles for the Atari 2600. Pong has also been included in several Atari compilations on platforms including the Sega Genesis, PlayStation Portable, Nintendo DS, and personal computer.[52][53][54][55][56] Through an agreement with Atari, Bally Gaming and Systems developed a slot machine version of the game.[57] The Atari published TD Overdrive includes Pong as an extra game which is played during the loading screen.[58][59] A 3Dplatform game with puzzle and shooter elements was reportedly in development by Atari Corporation for the Atari Jaguar in September 1995 under the title Pong 2000, as part of their series of arcade game updates for the system and was set to have an original storyline for it,[60][61] but it was never released. In 1999, the game was remade for home computers and the PlayStation with 3D graphics and power-ups.[62][63] In 2012, Atari celebrated the 40th anniversary of Pong by releasing Pong World.[64]

In popular culture[edit]

The game is featured in episodes of television series including That '70s Show,[65]King of the Hill[66] and Saturday Night Live.[67] In 2006, an American Express commercial featured Andy Roddick in a tennis match against the white, in-game paddle.[68] Other video games have also referenced and parodied Pong; for example Neuromancer for the Commodore 64 and Banjo-Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts for the Xbox 360.[69][70] The concert event Video Games Live has performed audio from Pong as part of a special retro 'Classic Arcade Medley'.[71]Frank Black's song 'Whatever Happened to Pong?' on the album Teenager of the Year references the game's elements.[72]

Dutch design studio Buro Vormkrijgers created a Pong-themed clock as a fun project within their offices. After the studio decided to manufacture it for retail, Atari took legal action in February 2006. The two companies eventually reached an agreement in which Buro Vormkrijgers could produce a limited number under license.[73] In 1999, French artist Pierre Huyghe created an installation titled 'Atari Light', in which two people use handheld gaming devices to play Pong on an illuminated ceiling. The work was shown at the Venice Biennale in 2001, and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León in 2007.[74] The game was included in the LondonBarbican Art Gallery's 2002 Game On exhibition meant to showcase the various aspects of video game history, development, and culture.[75]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^'Pong'. Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ abcSellers, John (August 2001). 'Pong'. Arcade Fever: The Fan's Guide to The Golden Age of Video Games. Running Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN0-7624-0937-1.

- ^ abcdefKent, Steven (2001). 'And Then There Was Pong'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 40–43. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abcdefEllis, David (2004). 'A Brief History of Video Games'. Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 3–4. ISBN0-375-72038-3.

- ^ abKent, Steven (2001). 'And Then There Was Pong'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^Kent, Steven (2001). 'Father of the Industry'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abcdefgShea, Cam (10 March 2008). 'Al Alcorn Interview'. IGN. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ abRapp, David (29 November 2006). 'The Mother of All Video Games'. American Heritage. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ abcHelgeson, Matt (March 2011). 'The Father of the Game Industry Returns to Atari'. Game Informer. GameStop (215): 39.

- ^'Video game history'. R. H. Baer Consultants. 1998. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^Baer, Ralph (April 2005). Video Games: In The Beginning. New Jersey, USA: Rolenta Press. p. 81. ISBN0-9643848-1-7.

- ^Morris, Dave (2004). 'Funky Town'. The Art of Game Worlds. HarperCollins. p. 166. ISBN0-06-072430-7.

- ^'Pong 40th anniversary - Rooster T. Feathers - Features & Columns'. www.metroactive.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^'Nov. 29, 1972: Pong, a Game Any Drunk Can Play'. WIRED. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^'Pong - CHM Revolution'. www.computerhistory.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^Goldberg, Harold. 'The Origins of the First Arcade Video Game: Atari's Pong'. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ abcdefKent, Steven (2001). 'And Then There Was Pong'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 43–45. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abKent, Steven (2001). 'The King and Court'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^'Production Numbers'(PDF). Atari. 1999. Archived(PDF) from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^'This Day in History: November 29'. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^Kent, Steven (2001). 'The Jackals'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 74. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abcdKent, Steven (2001). 'Could You Repeat That Two More Times?'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 80–83. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abKent, Steven L/ (2001). the Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^Kent, Steven (2001). 'Could You Repeat That Two More Times?'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 84–87. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abcLoguidice, Bill; Matt Barton (9 January 2009). 'The History Of Pong: Avoid Missing Game to Start Industry'. Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ abcdBaer, Ralph (1998). 'Genesis: How the Home Video Games Industry Began'. R. H. Baer Consultants. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^'Magnavox Sues Firms Making Video Games, Charges Infringement'. The Wall Street Journal. 17 April 1974.

- ^ abcdKent, Steven (2001). 'And Then There Was Pong'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 45–48. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^Nolan Bushnell (2003). The Story of Computer Games (video). Discovery Channel.

- ^Kent, Steven (2001). 'A Case of Two Gorillas'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 201. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abKent, Steven (2001). 'The King and Court'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abEllis, David (2004). 'Arcade Classics'. Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. p. 400. ISBN0-375-72038-3.

- ^ abcKent, Steven (2001). 'The Jackals'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abKent, Steven (2001). 'The King and Court'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 58. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abcEllis, David (2004). 'Dedicated Consoles'. Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 33–36. ISBN0-375-72038-3.

- ^ abcKent, Steven (2001). 'Strange Bedfellows'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ abSheff, David (1993). 'In Heaven's Hands'. Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children (1st ed.). Random House. pp. 26–28. ISBN0-679-40469-4.

- ^Ellis, David (2004). 'Dedicated Consoles'. Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 37–41. ISBN0-375-72038-3.

- ^'Pong'. IGN. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^'Top 100 Games of All Time'. Next Generation. No. 21. Imagine Media. September 1996. p. 47.

- ^Morales, Aaron (25 January 2013). 'The 10 best Atari games'. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^Retro Gamer Staff (August 2008). 'Developer Lookback: Konami Part I'. Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (53): 25.

- ^'What the Hell has Nolan Bushnell Started?'. Next Generation. Imagine Media (4): 11. April 1995.

- ^'Pong Doubles'. Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^'Quadrapong'. Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^'Doctor Pong'. Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^'Puppy Pong'. Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^'Snoopy Pong'. Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^Ellis, David (2004). 'Dedicated Consoles'. Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 402. ISBN0-375-72038-3.

- ^Kent, Steven (2001). 'The Jackals'. Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 71. ISBN0-7615-3643-4.

- ^Nelson, Mark (21 August 2007). 'Breaking Down Breakout: System And Level Design For Breakout-style Games'. Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^'Arcade Classics'. IGN. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^Atari (20 December 2007). 'Retro Arcade Masterpieces Hit Store Shelves in Atari Classics Evolved'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^Gerstmann, Jeff (23 March 2005). 'Retro Atari Classics Review'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^'Atari: 80 Classic Games in One Company Line'. GameSpot. 23 April 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^Kohler, Chris (7 September 2004). 'Atari opens up massive classic-game library'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^'Atari, Alliance Gaming to Develop Slots Based on Atari Video Games'. GameSpot. 9 September 2004. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^Munk, Simon (4 May 2002). 'PS2 Review: TD Overdrive'. Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^Gestalt (18 August 2002). 'TD Overdrive Xbox Review'. Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^Gore, Chris (September 1995). 'The Gorescore - Industry News You Can - The Return of Pong'. VideoGames - The Ultimate Gaming Magazine. No. 80. L.F.P., Inc. p. 20.

- ^Schmudde (5 November 2014). 'Lost interview with Francois Yves Bertrand'. AtariAge. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^'Pong: The Next Level (PC)'. IGN. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^'Pong: The Next Level (PlayStation)'. IGN. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^'Atari celebrates 40 years of Pong with new, free iOS Pong game, custom portable Xbox 360'. Engadget. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^'Punk Chick'. That '70s Show. Season 1. Episode 22. 21 June 1999. Fox Broadcasting Company.

- ^'It Ain't Over 'Til the Fat Neighbor Sings'. King of the Hill. Season 9. Episode 15. 15 May 2005. Fox Broadcasting Company.

- ^'Episode 5'. Saturday Night Live. Season 1. Episode 5. New York City. 15 November 1975. NBC.

- ^Ashcraft, Brian (22 August 2006). 'Roddick vs. Pong'. Kotaku. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^Parker, Sam (13 February 2004). 'The Greatest Games of All Time: Neuromancer'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^Anderson, Luke (11 September 2008). 'Banjo-Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts Updated Hands-On'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^Microsoft (28 August 2007). 'Microsoft Brings Video Games Live To London'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 19 July 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^Frank Black (Singer) (23 May 1994). Album: Teenager of the Year Song: Whatever Happened to Pong?. Elektra Records.

- ^Crecente, Brian (28 February 2006). 'Atari Threatens Pong Clock Makers'. Kotaku. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^'Tech rewind: Interesting facts about the hit arcade video game Pong'. Mid Day. 29 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^Boyes, Emma (9 October 2006). 'London museum showcases games'. GameSpot. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

Further reading[edit]

- Cohen, Scott (1984). Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari. McGraw-Hill. ISBN978-0-07-011543-9.

- Herman, Leonard (1997). Phoenix: The Fall & Rise of Videogames. Rolenta Press. ISBN978-0-9643848-2-8.

- Kline, Stephen; Dyer-Witheford, Nick; De Peuter, Greig (2003). Digital Play: The interaction of Technology, Culture and Marketing. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN978-0-7735-2591-7.

- Lowood, H. (2009). 'Videogames in Computer Space: The Complex History of Pong'. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 31 (3). pp. 5–19. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2009.53.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pong. |

- Pong-story.com, comprehensive site about Pong and its origins. Archived 13 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- The Atari Museum An in-depth look at Atari and its history

- Pong variants at MobyGames

| Highest governing body | ITTF |

|---|---|

| First played | 1880s Victorian England[1][2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Team members | Single or doubles |

| Type | Racquet sport, indoor |

| Equipment | Poly, 40 mm (1.57 in), 2.7 g (0.095 oz) |

| Glossary | Glossary of table tennis |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Since 1988 |

| Paralympic | Since inaugural 1960 Summer Paralympics |

Table tennis, also known as ping-pong, is a sport in which two or four players hit a lightweight ball back and forth across a table using small rackets. The game takes place on a hard table divided by a net. Except for the initial serve, the rules are generally as follows: players must allow a ball played toward them to bounce one time on their side of the table, and must return it so that it bounces on the opposite side at least once. A point is scored when a player fails to return the ball within the rules. Play is fast and demands quick reactions. Spinning the ball alters its trajectory and limits an opponent's options, giving the hitter a great advantage.

Table tennis is governed by the worldwide organization International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF), founded in 1926. ITTF currently includes 226 member associations.[3] The table tennis official rules are specified in the ITTF handbook.[4] Table tennis has been an Olympic sport since 1988,[5] with several event categories. From 1988 until 2004, these were men's singles, women's singles, men's doubles and women's doubles. Since 2008, a team event has been played instead of the doubles.

- 1History

- 2Equipment

- 3Gameplay

- 4Grips

- 5Types of strokes

- 5.1Offensive strokes

- 5.2Defensive strokes

- 6Effects of spin

History

The sport originated in Victorian England, where it was played among the upper-class as an after-dinner parlour game.[1][2] It has been suggested that makeshift versions of the game were developed by British military officers in India in around 1860s or 1870s, who brought it back with them.[6] A row of books stood up along the center of the table as a net, two more books served as rackets and were used to continuously hit a golf-ball.[7][8]

The name 'ping-pong' was in wide use before British manufacturer J. Jaques & Son Ltdtrademarked it in 1901. The name 'ping-pong' then came to describe the game played using the rather expensive Jaques's equipment, with other manufacturers calling it table tennis. A similar situation arose in the United States, where Jaques sold the rights to the 'ping-pong' name to Parker Brothers. Parker Brothers then enforced its trademark for the term in the 1920s making the various associations change their names to 'table tennis' instead of the more common, but trademarked, term.[9]

The next major innovation was by James W. Gibb, a British enthusiast of table tennis, who discovered novelty celluloid balls on a trip to the US in 1901 and found them to be ideal for the game. This was followed by E.C. Goode who, in 1901, invented the modern version of the racket by fixing a sheet of pimpled, or stippled, rubber to the wooden blade. Table tennis was growing in popularity by 1901 to the extent that tournaments were being organized, books being written on the subject,[7] and an unofficial world championship was held in 1902.

In 1921, the Table Tennis Association was founded, and in 1926 renamed the English Table Tennis Association.[10] The International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) followed in 1926.[1][11] London hosted the first official World Championships in 1926. In 1933, the United States Table Tennis Association, now called USA Table Tennis, was formed.[1][12]

In the 1930s, Edgar Snow commented in Red Star Over China that the Communist forces in the Chinese Civil War had a 'passion for the English game of table tennis' which he found 'bizarre'.[13] On the other hand, the popularity of the sport waned in 1930s Soviet Union, partly because of the promotion of team and military sports, and partly because of a theory that the game had adverse health effects.[14]

In the 1950s, paddles that used a rubber sheet combined with an underlying sponge layer changed the game dramatically,[1] introducing greater spin and speed.[15] These were introduced to Britain by sports goods manufacturer S.W. Hancock Ltd. The use of speed glue increased the spin and speed even further, resulting in changes to the equipment to 'slow the game down'. Table tennis was introduced as an Olympic sport at the Olympics in 1988.[16]

Rule changes

After the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, the ITTF instituted several rule changes that were aimed at making table tennis more viable as a televised spectator sport.[17][18] First, the older 38 mm (1.50 in) balls were officially replaced by 40 mm (1.57 in) balls in October 2000.[7][19] This increased the ball's air resistance and effectively slowed down the game. By that time, players had begun increasing the thickness of the fast sponge layer on their paddles, which made the game excessively fast and difficult to watch on television. A few months later, the ITTF changed from a 21-point to an 11-point scoring system (and the serve rotation was reduced from five points to two), effective in September 2001.[7] This was intended to make games more fast-paced and exciting. The ITTF also changed the rules on service to prevent a player from hiding the ball during service, in order to increase the average length of rallies and to reduce the server's advantage, effective in 2002.[20]For the opponent to have time to realize a serve is taking place, the ball must be tossed a minimum of 16 centimetres (6.3 in) in the air. The ITTF states that all events after July 2014 are played with a new poly material ball.[21][22]

Equipment

Ball

The international rules specify that the game is played with a sphere having a mass of 2.7 grams (0.095 oz) and a diameter of 40 millimetres (1.57 in).[23] The rules say that the ball shall bounce up 24–26 cm (9.4–10.2 in) when dropped from a height of 30.5 cm (12.0 in) onto a standard steel block thereby having a coefficient of restitution of 0.89 to 0.92. Balls are now made of a polymer instead of celluloid as of 2015, colored white or orange, with a matte finish. The choice of ball color is made according to the table color and its surroundings. For example, a white ball is easier to see on a green or blue table than it is on a grey table. Manufacturers often indicate the quality of the ball with a star rating system, usually from one to three, three being the highest grade. As this system is not standard across manufacturers, the only way a ball may be used in official competition is upon ITTF approval[23] (the ITTF approval can be seen printed on the ball).

The 40 mm ball was introduced after the end of the 2000 Summer Olympics.[19] This created some controversies. Then World No 1 table tennis professional Vladimir Samsonov threatened to pull out of the World Cup, which was scheduled to debut the new regulation ball on October 12, 2000.[24]

Table

The table is 2.74 m (9.0 ft) long, 1.525 m (5.0 ft) wide, and 76 cm (2.5 ft) high with any continuous material so long as the table yields a uniform bounce of about 23 cm (9.1 in) when a standard ball is dropped onto it from a height of 30 cm (11.8 in), or about 77%.[25][26] The table or playing surface is uniformly dark coloured and matte, divided into two halves by a net at 15.25 cm (6.0 in) in height. The ITTF approves only wooden tables or their derivates. Concrete tables with a steel net or a solid concrete partition are sometimes available in outside public spaces, such as parks.[27]

Racket/paddle

Players are equipped with a laminated wooden racket covered with rubber on one or two sides depending on the grip of the player. The ITTF uses the term 'racket',[28] though 'bat' is common in Britain, and 'paddle' in the U.S. and Canada.

The wooden portion of the racket, often referred to as the 'blade', commonly features anywhere between one and seven plies of wood, though cork, glass fiber, carbon fiber, aluminum fiber, and Kevlar are sometimes used. According to the ITTF regulations, at least 85% of the blade by thickness shall be of natural wood.[29] Common wood types include balsa, limba, and cypress or 'hinoki', which is popular in Japan. The average size of the blade is about 17 centimetres (6.7 in) long and 15 centimetres (5.9 in) wide, although the official restrictions only focus on the flatness and rigidity of the blade itself, these dimensions are optimal for most play styles.

Table tennis regulations allow different surfaces on each side of the racket.[30] Various types of surfaces provide various levels of spin or speed, and in some cases they nullify spin. For example, a player may have a rubber that provides much spin on one side of their racket, and one that provides no spin on the other. By flipping the racket in play, different types of returns are possible. To help a player distinguish between the rubber used by his opposing player, international rules specify that one side must be red while the other side must be black.[29] The player has the right to inspect their opponent's racket before a match to see the type of rubber used and what colour it is. Despite high speed play and rapid exchanges, a player can see clearly what side of the racket was used to hit the ball. Current rules state that, unless damaged in play, the racket cannot be exchanged for another racket at any time during a match.[31]

Gameplay

Starting a game

According to ITTF rule 2.13.1, the first service is decided by lot,[32] normally a coin toss.[33] It is also common for one player (or the umpire/scorer) to hide the ball in one or the other hand, usually hidden under the table, allowing the other player to guess which hand the ball is in. The correct or incorrect guess gives the 'winner' the option to choose to serve, receive, or to choose which side of the table to use. (A common but non-sanctioned method is for the players to play the ball back and forth three times and then play out the point. This is commonly referred to as 'serve to play', 'rally to serve', 'play for serve', or 'volley for serve'.)

Service and return

In game play, the player serving the ball commences a play.[34] The server first stands with the ball held on the open palm of the hand not carrying the paddle, called the freehand, and tosses the ball directly upward without spin, at least 16 cm (6.3 in) high.[35] The server strikes the ball with the racket on the ball's descent so that it touches first his court and then touches directly the receiver's court without touching the net assembly. In casual games, many players do not toss the ball upward; however, this is technically illegal and can give the serving player an unfair advantage.

The ball must remain behind the endline and above the upper surface of the table, known as the playing surface, at all times during the service. The server cannot use his/her body or clothing to obstruct sight of the ball; the opponent and the umpire must have a clear view of the ball at all times. If the umpire is doubtful of the legality of a service they may first interrupt play and give a warning to the server. If the serve is a clear failure or is doubted again by the umpire after the warning, the receiver scores a point.

If the service is 'good', then the receiver must make a 'good' return by hitting the ball back before it bounces a second time on receiver's side of the table so that the ball passes the net and touches the opponent's court, either directly or after touching the net assembly.[36] Thereafter, the server and receiver must alternately make a return until the rally is over. Returning the serve is one of the most difficult parts of the game, as the server's first move is often the least predictable and thus most advantageous shot due to the numerous spin and speed choices at his or her disposal.

Let

A Let is a rally of which the result is not scored, and is called in the following circumstances:[37]

- The ball touches the net in service (service), provided the service is otherwise correct or the ball is obstructed by the player on the receiving side. Obstruction means a player touches the ball when it is above or traveling towards the playing surface, not having touched the player's court since last being struck by the player.

- When the player on the receiving side is not ready and the service is delivered.

- Player's failure to make a service or a return or to comply with the Laws is due to a disturbance outside the control of the player.

- Play is interrupted by the umpire or assistant umpire.

A let is also called foul service, if the ball hits the server's side of the table, if the ball does not pass further than the edge and if the ball hits the table edge and hits the net.

Scoring

A point is scored by the player for any of several results of the rally:[38]

- The opponent fails to make a correct service or return.

- After making a service or a return, the ball touches anything other than the net assembly before being struck by the opponent.

- The ball passes over the player's court or beyond their end line without touching their court, after being struck by the opponent.

- The opponent obstructs the ball.

- The opponent strikes the ball twice successively. Note that the hand that is holding the racket counts as part of the racket and that making a good return off one's hand or fingers is allowed. It is not a fault if the ball accidentally hits one's hand or fingers and then subsequently hits the racket.

- The opponent strikes the ball with a side of the racket blade whose surface is not covered with rubber.

- The opponent moves the playing surface or touches the net assembly.

- The opponent's free hand touches the playing surface.

- As a receiver under the expedite system, completing 13 returns in a rally.[39]

- The opponent that has been warned by the umpire commits a second offense in the same individual match or team match. If the third offence happens, 2 points will be given to the player.[40] If the individual match or the team match has not ended, any unused penalty points can be transferred to the next game of that match.[33]

A game shall be won by the player first scoring 11 points unless both players score 10 points, when the game shall be won by the first player subsequently gaining a lead of 2 points. A match shall consist of the best of any odd number of games.[41] In competition play, matches are typically best of five or seven games.

Alternation of services and ends

Service alternates between opponents every two points (regardless of winner of the rally) until the end of the game, unless both players score ten points or the expedite system is operated, when the sequences of serving and receiving stay the same but each player serves for only one point in turn (Deuce).[42] The player serving first in a game receives first in the next game of the match.

After each game, players switch sides of the table. In the last possible game of a match, for example the seventh game in a best of seven matches, players change ends when the first player scores five points, regardless of whose turn it is to serve. If the sequence of serving and receiving is out of turn or the ends are not changed, points scored in the wrong situation are still calculated and the game shall be resumed with the order at the score that has been reached.

Doubles game

In addition to games between individual players, pairs may also play table tennis. Singles and doubles are both played in international competition, including the Olympic Games since 1988 and the Commonwealth Games since 2002.[43] In 2005, the ITTF announced that doubles table tennis only was featured as a part of team events in the 2008 Olympics.

In doubles, all the rules of single play are applied except for the following.

Service

- A line painted along the long axis of the table to create doubles courts bisects the table. This line's only purpose is to facilitate the doubles service rule, which is that service must originate from the right hand 'box' in such a way that the first bounce of the serve bounces once in said right hand box and then must bounce at least once in the opponent side's right hand box (far left box for server), or the receiving pair score a point.[35]

Order of play, serving and receiving

- Players must hit the ball in turn. For example, if A is paired with B, X is paired with Y, A is the server and X is the receiver. The order of play shall be A→X→B→Y. The rally proceeds this way until one side fails to make a legal return and the other side scores.[44]

- At each change of service, the previous receiver shall become the server and the partner of the previous server shall become the receiver. For example, if the previous order of play is A→X→B→Y, the order becomes X→B→Y→A after the change of service.[42]

- In the second or the latter games of a match, the game begins in reverse order of play. For example, if the order of play is A→X→B→Y at beginning of the first game, the order begins with X→A→Y→B or Y→B→X→A in the second game depending on either X or Y being chosen as the first server of the game. That means the first receiver of the game is the player who served to the first server of the game in the preceding game. In each game of a doubles match, the pair having the right to serve first shall choose which of them will do so. The receiving pair, however, can only choose in the first game of the match.

- When a pair reaches 5 points in the final game, the pairs must switch ends of the table and change the receiver to reverse the order of play. For example, when the last order of play before a pair score 5 points in the final game is A→X→B→Y, the order after change shall be A→Y→B→X if A still has the second serve. Otherwise, X is the next server and the order becomes X→A→Y→B.

Men's doubles. Brothers Dmitry Mazunov and Andrey Mazunov in 1989.

Women's doubles finals, 2013 World Table Tennis Championships.

Mixed doubles finals, 2013 World Table Tennis Championships.

Expedite system

If a game is unfinished after 10 minutes' play and fewer than 18 points have been scored, the expedite system is initiated.[39] The umpire interrupts the game, and the game resumes with players serving for one point in turn. If the expedite system is introduced while the ball is not in play, the previous receiver shall serve first. Under the expedite system, the server must win the point before the opponent makes 13 consecutive returns or the point goes to the opponent. The system can also be initiated at any time at the request of both players or pairs. Once introduced, the expedite system remains in force until the end of the match. A rule to shorten the time of a match, it is mainly seen in defensive players' games.

Grips

Though table tennis players grip their rackets in various ways, their grips can be classified into two major families of styles, penhold and shakehand.[45] The rules of table tennis do not prescribe the manner in which one must grip the racket, and numerous grips are employed.

Penhold

The penhold grip is so-named because one grips the racket similarly to the way one holds a writing instrument.[46] The style of play among penhold players can vary greatly from player to player. The most popular style, usually referred to as the Chinese penhold style, involves curling the middle, ring, and fourth finger on the back of the blade with the three fingers always touching one another.[46] Chinese penholders favour a round racket head, for a more over-the-table style of play. In contrast, another style, sometimes referred to as the Japanese/Korean penhold grip, involves splaying those three fingers out across the back of the racket, usually with all three fingers touching the back of the racket, rather than stacked upon one another.[46] Sometimes a combination of the two styles occurs, wherein the middle, ring and fourth fingers are straight, but still stacked, or where all fingers may be touching the back of the racket, but are also in contact with one another. Japanese and Korean penholders will often use a square-headed racket for an away-from-the-table style of play. Traditionally these square-headed rackets feature a block of cork on top of the handle, as well as a thin layer of cork on the back of the racket, for increased grip and comfort. Penhold styles are popular among players originating from East Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Traditionally, penhold players use only one side of the racket to hit the ball during normal play, and the side which is in contact with the last three fingers is generally not used. This configuration is sometimes referred to as 'traditional penhold' and is more commonly found in square-headed racket styles. However, the Chinese developed a technique in the 1990s in which a penholder uses both sides of the racket to hit the ball, where the player produces a backhand stroke (most often topspin) known as a reverse penhold backhand by turning the traditional side of the racket to face one's self, and striking the ball with the opposite side of the racket. This stroke has greatly improved and strengthened the penhold style both physically and psychologically, as it eliminates the strategic weakness of the traditional penhold backhand.

Shakehand

The shakehand grip is so-named because the racket is grasped as if one is performing a handshake.[47] Though it is sometimes referred to as the 'tennis' or 'Western' grip, it bears no relation to the Western tennis grip, which was popularized on the West Coast of the United States in which the racket is rotated 90°, and played with the wrist turned so that on impact the knuckles face the target. In table tennis, 'Western' refers to Western nations, for this is the grip that players native to Europe and the Americas have almost exclusively employed.

The shakehand grip's simplicity and versatility, coupled with the acceptance among top-level Chinese trainers that the European style of play should be emulated and trained against, has established it as a common grip even in China.[48] Many world class European and East Asian players currently use the shakehand grip, and it is generally accepted that shakehands is easier to learn than penholder, allowing a broader range of playing styles both offensive and defensive.[49]

Seemiller

The Seemiller grip is named after the American table tennis champion Danny Seemiller, who used it. It is achieved by placing the thumb and index finger on either side of the bottom of the racquet head and holding the handle with the rest of the fingers. Since only one side of the racquet is used to hit the ball, two contrasting rubber types can be applied to the blade, offering the advantage of 'twiddling' the racket to fool the opponent. Seemiller paired inverted rubber with anti-spin rubber. Many players today combine inverted and long-pipped rubber. The grip is considered exceptional for blocking, especially on the backhand side, and for forehand loops of backspin balls.[50]The Seemiller grip's popularity reached its apex in 1985 when four (Danny Seemiller, Ricky Seemiller, Eric Boggan and Brian Masters) of the United States' five participants in the World Championships used it.[50]Jean-jacques rousseau quotes.

Shakehand grip (Vladimir Samsonov)

Chinese penhold (Ma Lin)

Traditional penhold (Ryu Seung-min)

Types of strokes

Table tennis strokes generally break down into offensive and defensive categories.

Offensive strokes

Hit

Also known as speed drive, a direct hit on the ball propelling it forward back to the opponent. This stroke differs from speed drives in other racket sports like tennis because the racket is primarily perpendicular to the direction of the stroke and most of the energy applied to the ball results in speed rather than spin, creating a shot that does not arc much, but is fast enough that it can be difficult to return. A speed drive is used mostly for keeping the ball in play, applying pressure on the opponent, and potentially opening up an opportunity for a more powerful attack.

Loop

Perfected during the 1960s,[1][51] the loop is essentially the reverse of the chop. The racket is parallel to the direction of the stroke ('closed') and the racket thus grazes the ball, resulting in a large amount of topspin. A good loop drive will arc quite a bit, and once striking the opponent's side of the table will jump forward, much like a kick serve in tennis. Most professional players nowadays, such as Ding Ning, Timo Boll and Zhang Jike, primarily use loop for offense.

Counter-hit

The counter-hit is usually a counterattack against drives, normally high loop drives. The racket is held closed and near to the ball, which is hit with a short movement 'off the bounce' (immediately after hitting the table) so that the ball travels faster to the other side. Kenta Matsudaira is known for primarily using counter-hit for offense.

Flip

When a player tries to attack a ball that has not bounced beyond the edge of the table, the player does not have the room to wind up in a backswing. The ball may still be attacked, however, and the resulting shot is called a flip because the backswing is compressed into a quick wrist action. A flip is not a single stroke and can resemble either a loop drive or a loop in its characteristics. What identifies the stroke is that the backswing is compressed into a short wrist flick.

Smash

A player will typically execute a smash when the opponent has returned a ball that bounces too high or too close to the net. It is nearly always done with a forehand stroke. Smashing use rapid acceleration to impart as much speed on the ball as possible so that the opponent cannot react in time. The racket is generally perpendicular to the direction of the stroke. Because the speed is the main aim of this shot, the spin on the ball is often minimal, although it can be applied as well. An offensive table tennis player will think of a rally as a build-up to a winning smash. Smash is used more often with penhold grip.

Defensive strokes

Push

The push (or 'slice' in Asia) is usually used for keeping the point alive and creating offensive opportunities. A push resembles a tennis slice: the racket cuts underneath the ball, imparting backspin and causing the ball to float slowly to the other side of the table. A push can be difficult to attack because the backspin on the ball causes it to drop toward the table upon striking the opponent's racket. In order to attack a push, a player must usually loop (if the push is long) or flip (if the push is short) the ball back over the net. Often, the best option for beginners is to simply push the ball back again, resulting in pushing rallies. Against good players, it may be the worst option because the opponent will counter with a loop, putting the first player in a defensive position. Pushing can have advantages in some circumstances, such as when the opponent makes easy mistakes.

Chop

A chop is the defensive, backspin counterpart to the offensive loop drive.[52] A chop is essentially a bigger, heavier push, taken well back from the table. The racket face points primarily horizontally, perhaps a little bit upward, and the direction of the stroke is straight down. The object of a defensive chop is to match the topspin of the opponent's shot with backspin. A good chop will float nearly horizontally back to the table, in some cases having so much backspin that the ball actually rises. Such a chop can be extremely difficult to return due to its enormous amount of backspin. Some defensive players can also impart no-spin or sidespin variations of the chop. Some famous choppers include Joo Sae-hyuk and Wu Yang.

Block

A block is executed by simply placing the racket in front of the ball right after the ball bounces; thus, the ball rebounds back toward the opponent with nearly as much energy as it came in with. This requires precision, since the ball's spin, speed, and location all influence the correct angle of a block. It is very possible for an opponent to execute a perfect loop, drive, or smash, only to have the blocked shot come back just as fast. Due to the power involved in offensive strokes, often an opponent simply cannot recover quickly enough to return the blocked shot, especially if the block is aimed at an unexpected side of the table. Blocks almost always produce the same spin as was received, many times topspin.

Ping Pong Video Game Pics

Lob

The defensive lob propels the ball about five metres in height, only to land on the opponent's side of the table with great amounts of spin.[53] The stroke itself consists of lifting the ball to an enormous height before it falls back to the opponent's side of the table. A lob can have nearly any kind of spin. Though the opponent may smash the ball hard and fast, a good defensive lob could be more difficult to return due to the unpredictability and heavy amounts of the spin on the ball.[53] Thus, though backed off the table by tens of feet and running to reach the ball, a good defensive player can still win the point using good lobs. Lob is used less frequently by professional players. A notable exception is Michael Maze.

Effects of spin

Adding spin onto the ball causes major changes in table tennis gameplay. Although nearly every stroke or serve creates some kind of spin, understanding the individual types of spin allows players to defend against and use different spins effectively.[54]

Backspin

Backspin is where the bottom half of the ball is rotating away from the player, and is imparted by striking the base of the ball with a downward movement.[54] At the professional level, backspin is usually used defensively in order to keep the ball low.[55] Backspin is commonly employed in service because it is harder to produce an offensive return, though at the professional level most people serve sidespin with either backspin or topspin. Due to the initial lift of the ball, there is a limit on how much speed with which one can hit the ball without missing the opponent's side of the table. However, backspin also makes it harder for the opponent to return the ball with great speed because of the required angular precision of the return. Alterations are frequently made to regulations regarding equipment in an effort to maintain a balance between defensive and offensive spin choices.[citation needed] It is actually possible to smash with backspin offensively, but only on high balls that are close to the net.

Topspin

The topspin stroke has a smaller influence on the first part of the ball-curve. Like the backspin stroke, however, the axis of spin remains roughly perpendicular to the trajectory of the ball thus allowing for the Magnus effect to dictate the subsequent curvature. After the apex of the curve, the ball dips downwards as it approaches the opposing side, before bouncing. On the bounce, the topspin will accelerate the ball, much in the same way that a wheel which is already spinning would accelerate upon making contact with the ground. When the opponent attempts to return the ball, the topspin causes the ball to jump upwards and the opponent is forced to compensate for the topspin by adjusting the angle of his or her racket. This is known as 'closing the racket'.

The speed limitation of the topspin stroke is minor compared to the backspin stroke. This stroke is the predominant technique used in professional competition because it gives the opponent less time to respond. In table tennis topspin is regarded as an offensive technique due to increased ball speed, lower bio-mechanical efficiency and the pressure that it puts on the opponent by reducing reaction time. (It is possible to play defensive topspin-lobs from far behind the table, but only highly skilled players use this stroke with any tactical efficiency.) Topspin is the least common type of spin to be found in service at the professional level, simply because it is much easier to attack a top-spin ball that is not moving at high speed.

Sidespin

This type of spin is predominantly employed during service, wherein the contact angle of the racket can be more easily varied. Unlike the two aforementioned techniques, sidespin causes the ball to spin on an axis which is vertical, rather than horizontal. The axis of rotation is still roughly perpendicular to the trajectory of the ball. In this circumstance, the Magnus effect will still dictate the curvature of the ball to some degree. Another difference is that unlike backspin and topspin, sidespin will have relatively very little effect on the bounce of the ball, much in the same way that a spinning top would not travel left or right if its axis of rotation were exactly vertical. This makes sidespin a useful weapon in service, because it is less easily recognized when bouncing, and the ball 'loses' less spin on the bounce. Sidespin can also be employed in offensive rally strokes, often from a greater distance, as an adjunct to topspin or backspin. This stroke is sometimes referred to as a 'hook'. The hook can even be used in some extreme cases to circumvent the net when away from the table.

Corkspin

Players employ this type of spin almost exclusively when serving, but at the professional level, it is also used from time to time in the lob. Unlike any of the techniques mentioned above, corkspin (or 'drill-spin') has the axis of spin relatively parallel to the ball's trajectory, so that the Magnus effect has little or no effect on the trajectory of a cork-spun ball: upon bouncing, the ball will dart right or left (according to the direction of the spin), severely complicating the return. In theory this type of spin produces the most obnoxious effects, but it is less strategically practical than sidespin or backspin, because of the limitations that it imposes upon the opponent during their return. Aside from the initial direction change when bouncing, unless it goes out of reach, the opponent can counter with either topspin or backspin. A backspin stroke is similar in the fact that the corkspin stroke has a lower maximum velocity, simply due to the contact angle of the racket when producing the stroke. To impart a spin on the ball which is parallel to its trajectory, the racket must be swung more or less perpendicular to the trajectory of the ball, greatly limiting the forward momentum that the racket transfers to the ball. Corkspin is almost always mixed with another variety of spin, since alone, it is not only less effective but also harder to produce.

Competition

Competitive table tennis is popular in East Asia and Europe, and has been[vague] gaining attention in the United States.[56] The most important international competitions are the World Table Tennis Championships, the Table Tennis World Cup, the Olympics and the ITTF World Tour. Continental competitions include the following:

Ping Pong Video Game For Cpu In Year 2000

- the Asian Championships

- the Asian Games

Chinese players have won 60% of the men's World Championships since 1959;[57] in the women's competition for the Corbillin Cup, Chinese players have won all but three of the World Championships since 1971.[58] Other strong teams come from East Asia and Europe, including countries such as Austria, Belarus, Germany, Hong Kong, Portugal, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Sweden, and Taiwan.[59]

There are also professional competitions at the clubs level; the respective leagues of Austria, Belgium, China (specifically, the China Table Tennis Super League), France, Germany and Russia are examples of the highest level. There are also some important international club teams competitions such as the European Champions League and its former competitor,[vague] the European Club Cup, where the top club teams from European countries compete.

Notable players

An official hall of fame exists at the ITTF Museum.[60] A Grand Slam is earned by a player who wins singles crowns at the Olympic Games, World Championships, and World Cup.[61]Jan-Ove Waldner of Sweden first completed the grand slam at 1992 Olympic Games. Deng Yaping of China is the first female recorded at the inaugural Women's World Cup in 1996. The following table presents an exhaustive list of all players to have completed a grand slam.

| Name | Gender | Nationality | Times won | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olympics | World Championships | World Cup | ||||

| Jan-Ove Waldner | Male | SWE | 1 (1992) | 2 (1989, 1997) | 1 (1990) | [62] |

| Deng Yaping | Female | China | 2 (1992, 1996) | 3 (1991, 1995, 1997) | 1 (1996) | [63] |

| Liu Guoliang | Male | China | 1 (1996) | 1 (1999) | 1 (1996) | [64] |

| Kong Linghui | Male | China | 1 (2000) | 1 (1995) | 1 (1995) | [65] |

| Wang Nan | Female | China | 1 (2000) | 3 (1999, 2001, 2003) | 4 (1997, 1998, 2003, 2007) | [66] |

| Zhang Yining | Female | China | 2 (2004, 2008) | 2 (2005, 2009) | 4 (2001, 2002, 2004, 2005) | [67] |

| Zhang Jike | Male | China | 1 (2012) | 2 (2011, 2013) | 2 (2011, 2014) | [68] |

| Li Xiaoxia | Female | China | 1 (2012) | 1 (2013) | 1 (2008) | [69] |

| Ding Ning | Female | China | 1 (2016) | 3 (2011, 2015, 2017) | 2 (2011, 2014) | [70] |

| Ma Long | Male | China | 1 (2016) | 3 (2015, 2017, 2019) | 2 (2012, 2015) | |

Jean-Philippe Gatien (France) and Wang Hao (China) won both the World Championships and the World Cup, but lost in the gold medal matches at the Olympics. Jörgen Persson (Sweden) also won the titles except the Olympic Games. Persson is one of the three table tennis players to have competed at seven Olympic Games. Ma Lin (China) won both the Olympic gold and the World Cup, but lost (three times, in 1999, 2005, and 2007) in the finals of the World Championships.

Governance

Founded in 1926, the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) is the worldwide governing body for table tennis, which maintains an international ranking system in addition to organizing events like the World Table Tennis Championships.[12] In 2007, the governance for table tennis for persons with a disability was transferred from the International Paralympic Committee to the ITTF.[71]

On many continents, there is a governing body responsible for table tennis on that continent. For example, the European Table Tennis Union (ETTU) is the governing body responsible for table tennis in Europe.[72] There are also national bodies and other local authorities responsible for the sport, such as USA Table Tennis (USATT), which is the national governing body for table tennis in the United States.[12]

See also

References

- ^ abcdefHodges 1993, p. 2

- ^ abLetts, Greg. 'A Brief History of Table Tennis/Ping-Pong'. About.com. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^'Member Associations'. ITTF. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2

- ^Hurt III, Harry (5 April 2008). 'Ping-Pong as Mind Game (Although a Good Topspin Helps)'. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^WashingtonPost.com. Accessed 2 August 2012. Archived 3 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- ^ abcd'A Comprehensive History of Table Tennis'. www.ittf.com. ITTF. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^Hamilton, Fiona (2 September 2008). 'Inventors of ping-pong say Mayor Boris Johnson is wrong'. The Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^Dean R. Karau (August 2008). 'Are There Any Trademark Rights Left In The Term Ping-Pong?'. www.fredlaw.com. Fredrikson & Byron, P.A. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011.

- ^M. Itoh. The Origin of Ping-Pong Diplomacy: The Forgotten Architect of Sino-U.S. Rapprochement. p. 1. ISBN9780230339354.

- ^'International Table Tennis Federation Archives'. www.ittf.com. ITTF. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ abc'About USATT'. United States Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^Edgar Snow, Red Star Over China, Grove Press, New York, 1938 (revised 1968), p 281.

- ^'Отечественная История настольного тенниса'. ttfr.ru. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^'Thick Sponge Bats 1950s'. www.ittf.com. ITTF. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^'Table Tennis in the Olympic Games'. www.ittf.com. ITTF. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^Clemett, Colin. 'Evolution of the Laws of Table Tennis and the Regulations for International Competitions'(PDF). ITTF Museum. ITTF. Archived from the original(PDF) on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^'Bigger ball after Olympics'. New Straits Times. Malaysia. 24 February 2000. p. 39. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ ab'Board of Directors Passes Use of 40mm Ball'. USA Table Tennis. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^'Sport takes plunge with new rule'. New Straits Times. Malaysia. 27 April 2001. p. 40. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^'BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING'(PDF). ITTF. Archived from the original(PDF) on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^'What Are the Origins of Table Tennis?'. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ ab'ITTF Technical Leaflet T3: The Ball'(PDF). ITTF. December 2009. p. 4. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^'BBC News TENNIS Table tennis gets bigger ball'. news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.1

- ^'ITTF Technical Leaflet T1: The Table'(PDF). ITTF. May 2013. Archived from the original(PDF) on 25 October 2013.

- ^Kaminer, Ariel (27 March 2011). 'The Joys of Ping-Pong in the Open'. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^2013 ITTF Branding GuidelinesArchived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 24 May 2014.

- ^ abInternational Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.4

- ^'ITTF Technical Leaflet T4: Racket Coverings'(PDF). ITTF. August 2010. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 3.4.2.4

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.13.1

- ^ ab'ITTF Handbook for Match Officials 13th edition'(PDF). ITTF. August 2007. Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.5

- ^ abInternational Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.6

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.7

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.5.3 and 2.9

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.5.4 and 2.10

- ^ abInternational Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.15

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 3.5.2

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.11 and 2.12

- ^ abInternational Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.13 and 2.14

- ^'ITTF statistics by event'. ITTF. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^International Table Tennis Federation 2011, index 2.8

- ^McAfee, Richard (2009). Table Tennis Steps to Success. Human Kinetics. p. 1. ISBN0-7360-7731-6.

- ^ abcHodges 1993, p. 13

- ^Hodges 1993, p. 10

- ^Hodges; Yinghua. The Secrets of Chinese Table Tennis.